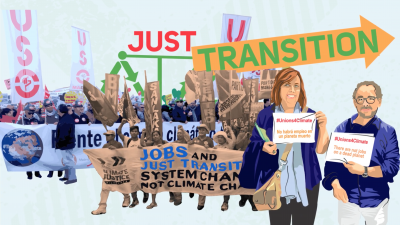

Just Transition in Agriculture

Just Transition has become an established discursive and conceptual framework to transition economic industries toward a low-carbon and climate-resilient future in the coal and mining industry. In other areas, like animal agriculture, which is equally damaging to the climate, Just Transition is not discussed or employed, despite being just as imperative.

Written by Charlotte E. Blattner

The Emergence of Just Transition

The world as we know it today hasn’t always been that way. Our railroad net was once small and sparse, energy production once was a fraction of what it is today, and supermarkets – if they existed at all – did not offer the mind-boggling menu of options we can choose from today. Many of these products, services, and institutions have not gradually found their way into our modern world, but they came about by massive and rapid changes in investments, economic policy, and large-scale transformations on an enterprise level.

As these changes took hold, people relying on previous systems and institutions often became vulnerable: they became economically vulnerable as they lost their jobs: think of carriage drivers, for example. Similarly, as we’re now adjusting to a changing climate, so do people become vulnerable to the broader socio-economic and legal changes: For example, coal workers affected by coal plant retirements are facing job loss and lack of employability. In fact, there are entire communities in coal-dominated towns that are threatened by declining tax revenues, infrastructure maintenance, and local services.

How do we, as a society deal with such challenges? Historically, we haven’t. People affected by such turnarounds were simply left unprotected. Today, however, this raises questions of solidarity, social justice issues, and duties of assistance by the state owed to its citizens. So in response to these challenges, in recent years, Just Transition emerged as a movement that (1) recognizes that a shift toward a climate-resilient and low-carbon economy is inevitable, and (2) which emphasizes that we must support workers and the broader communities affected by economic restructuring. In short: “Transition is inevitable, justice is not.” The rationale of concept of Just Transition is that the downsides of economic transitions should not alone be borne by individuals and communities who were previously thought to provide valuable services to the public, such as by producing energy. Instead, it is the public’s responsibility, as a whole, to ensure that transitions, which are necessary, are also just.

The Just Transition movement gained a foothold internationally when, in 2010, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) unanimously adopted Just Transition as a framework for climate change challenges, expressing that it is “committed to promoting an integrated approach to sustainable development through a just transition where social progress, environmental protection and economic needs are brought into a framework of democratic governance, where labour and other human rights are respected and gender equality is achieved” (ITUC, 2010, p. 1, para. 2) Five years later, in 2015, the International Labor Organization (ILO) adopted Guidelines for a Just Transition Towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All. At the Paris climate conference (COP 21), which took place the same year, 195 countries signed the Paris Agreement and enshrined in its preamble: “Taking into account the imperatives of a Just Transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities.” (Paris Agreement, 2015, p. 2, preamble)

This conviction, as it should, has found its way into domestic policies, such as in the EU’s Just Transition Mechanism or with regard to the U.S. Green New Deal. The Canadian government was one of the first to commission a task force to sketch a just transition for Canadian coal power workers and communities. In February 2019, the Task Force published its concluding report. It found that the federal government has a duty to prepare communities that are economically dependent on coal, for a future when their products aren’t needed, and demanded that its proposed policies to achieve this goal be written into legislation. Just Transition thus is now widely accepted as a guiding framework to adapt and, in some cases, reform economic sectors in response to climate change challenges.

Animal Agriculture as the ‘New Coal’

Just Transition’s primary application is in the coal and mining industry. But as the world aims to transition to a zero-carbon society, other sectors contributing to global warming, too, are subject to decarbonization and, hence, Just Transition. Here, I focus on agriculture, particularly animal agriculture, as such a sector we should be focusing on.

Animal agriculture today accounts for at least 16.5% of all GHG emissions, more than the worldwide transport sector (Twine 2021), and it causes 32% of global anthropogenic methane emissions, which is more than what’s coming from gas, oil and coal production (UNEP and CCAC 2021).

Animal agriculture also is one of the key drivers of:

- Soil degradation, aquatic habitat destruction (both freshwater and oceanic ecosystems), air pollution, water contamination and biodiversity loss

- Loss of livelihoods and compromised food sovereignty, as well as reduced employment and poverty in rural areas

- Global hunger and malnutrition

- Poor working conditions in the meat processing industry

- High animal-based food consumption being detrimental to human health and increasing public health costs

- Main driver of zoonotic diseases

- Overuse of antibiotics in animals leading to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) (50by40 2021)

These facts have led the United Nations to acknowledge that animal agriculture today is “one of the most important drivers of environmental pressures” and the reduction of these pressures “would only be possible with a substantial worldwide diet change, away from animal products” (UNEP, 2010, p. 82). Nine years later, the IPCC came to a similar conclusion, but formulated this positively: “Balanced diets, featuring plant-based foods, such as those based on coarse grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds, and animal-sourced food produced in resilient, sustainable and low-GHG emission systems, present major opportunities for adaptation and mitigation while generating significant co-benefits in terms of human health” (IPCC, 2019, p. 26). Despite this knowledge and its endorsement by key international players, transitions are not happening in the agricultural sector.

Agriculture as a Blind Spot of Climate Policy

In the 2015 Paris Agreement, 196 countries pledged to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. To achieve the latter goal – on which decent human life and the flourishing of animals and nature, more broadly, depends – globally, CO2 emissions would need to be reduced by 45% by 2030 compared to 2010 . The newest UN Climate Change’s Synthesis Report , analysing solely countries’ commitment with reference to the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), shows that the world is not at all on track to meet the Paris Agreement goals. Based on the level of ambition communicated through existing NDCs, countries’ total emissions – if NDCs were perfectly enforced – would be reduced by 9%, in 2030 compared to 2010. Part of the problem is that countries do not consider agriculture in climate policy, hence they ignore agriculture as a sector worth setting NDCs for or they do so insufficiently.

Most Paris Agreement signatories mention agriculture in their nationally determined contributions (NDCs), with some including animal agriculture. Almost all of these stress the importance of increasing production, intensification and finding technical ‘solutions’. However, already today, the growing demand for animal protein is satisfied mostly by intensified production in factory farms (also known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs), where animals are housed indoors in extreme confinement, and which adds pressures to the environment (through land, air, and water pollution and excessive use of resources) and gives rise to significant social justice issues (e.g., environmental racism and hazardous jobs in meatpacking and at the slaughterhouse) (Blattner & Ammann 2020). So, one would think de-intensification, more local and organic production would be the solution, but as meta research by the Oxford University, using the yet most comprehensive database, shows: even the most de-intensified and organic animal products vastly outpace plant-based foods in terms of their carbon forkprint (Poore & Nemecek 2018). A change in production and consumption toward plant-based foods, by contrast, would reduce emissions by up to 73%, drop freshwater withdrawal by a quarter and free up 76% farmland (id.).

It’s clear that reducing emissions from fossil fuels is essential for meeting the Paris Agreement goals, however, the current insulation of agriculture from the reach of climate policy thwarts this goal. New research shows that even if fossil fuel emissions were immediately halted, current trends in global food systems would prevent staying within the 1.5°C limit and, by the end of the century, even a global warming of below 2°C is threatened (Clark et al. 2020; Leahy et al. 2020; Wollenberg et al 2016). So if animal agriculture has become the most polluting way to produce food, just as coal is the most polluting way to produce energy, then the call for phasing out animal agriculture is not only justified, but long overdue.

One reason for the lack of political attention paid to animal agriculture seems to be that the industry has long enjoyed a privileged status in law. Agricultural exceptionalism has for decades insulated agricultural producers from regulation, in a range of fields including trade, environmental protection, labor and employment law, and animal protection (Blattner & Ammann 2020). Another reason might be that many people consider their food choices to be beyond the grasp of law and politics. As a consequence, diet change for a common future is seen as a voluntary move, subject to each person’s own decision. This seems odd because the same piecemeal approach could have been used when it comes to coal: “Let energy consumers decide for themselves!” Yet there was broad acknowledgment for the need to phase out coal precisely because the industry contributes tremendously to climate change – regardless of how “private” we intuitively consider such use.

The Need for Just Transition in Agriculture

From a climate perspective, the failure to apply the Just Transition principles to agriculture is irrational, irresponsible and incompatible with our international commitments. It is irrational because coal and agriculture both produce significant amounts of GHG emissions, yet, only one sector is subject to discontinuation (see also Bähr 2015). And while coal alternatives, arguably, are expensive or must yet be produced and designed, alternatives to carbon-heavy agriculture (especially in the form of diet change) are fully available and accessible. Keeping up a policy dichotomy between coal and animal agriculture is also irresponsible because as governments focus on coal alone, valuable years of curbing climate change are lost. Further, continuing business as usual in the way we raise animals is incompatible with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs – notably goals 3, 6, 12, 14 & 15), the Paris Agreement and other critical international targets.

The insulation of agriculture from climate law and policy is also irresponsible vis-à-vis agricultural workers. Today, individual farmers bear the brunt of transitioning toward carbon-neutral production. They have to develop new business models, retrain their personnel, stem the financial burden, and deal with social stigma. However, we have a responsibility to share here: as consumers, as the ones driving demand, as providers of subsidies, as governments and so on. Farmers – like coal miners – need their community and governments to support them in this process. Just Transition, by working toward sound investments, social dialogue, research-based impact assessments, social protection, and economic diversification, must be part of this equation.

Conclusion

Be it on the international, state, local, or community level, it is time that we acknowledge agriculture as a blind spot in climate politics; that we begin a conversation about the risks that we thereby create for society, farmers, consumers, and future generations; and that we embark on these challenges together, through collective empowerment, rather than through antagonism, denial, and fear — dynamics that currently frame the discussion around agricultural policy.

Just Transition for agriculture, demanding at least the discontinuation of the most polluting ways to produce food, i.e. animal agriculture, should be centered for discussion at established international organizations like the ILO, the UN, FAO, and IPCC. A first step to operationalize is to produce more research that details affected subsectors and end goals, and shows how a transition could be initiated, who should be involved, how it could be financed, and what the process should look like so that the framework succeeds at being just for all. It might sound tedious to change the status quo, but let’s not forget that the upshot of exploring transition in agriculture is, most obviously, having another, an additional much-needed route to stabilize the climate, and tackling the range of social and environmental hazards animal agriculture currently produces.

First published as Charlotte E. Blattner, Just Transition for Agriculture? A Critical Step in Tackling Climate Change, 9(3) Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems and Community Development 53-58 (2020). https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2020.093.006

Photo credit: IndustriALL